Read the Original Article Here.

Published By “Monterey County: TheWeekly Insider” written by: Asaf Shalev; Jan 16, 2020

More than 70 languages or dialects have been offered by the Defense Language Institute, whose Monterey headquarters has awarded more than 15,000 associate degrees to service members since the 1980s.

TO KILL IRANIAN COMMANDER GEN. QASSEM SOLEIMANI, U.S. forces had to know exactly where the leader of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps’ Quds Force was located at all times, which requires sophisticated surveillance. In justifying an assassination of a major political figure, the Trump administration is saying that he posed a “near term” threat to national security, which suggests it had decisive intelligence.

Whether or not the justification for the killing ultimately holds up, the information our military and spy agencies possess, and how they gather it, have come into sharper focus. One of the foundations of intelligence is knowing the languages of foreign powers. For that, the Pentagon relies on the Defense Language Institute in Monterey. Established during World War II, the school today trains thousands of military and other federal personnel every year in about 20 different languages and dialects. (DLI teaches additional languages off-campus on a smaller scale, through contractors.) Many consider it the premier language school in the world.

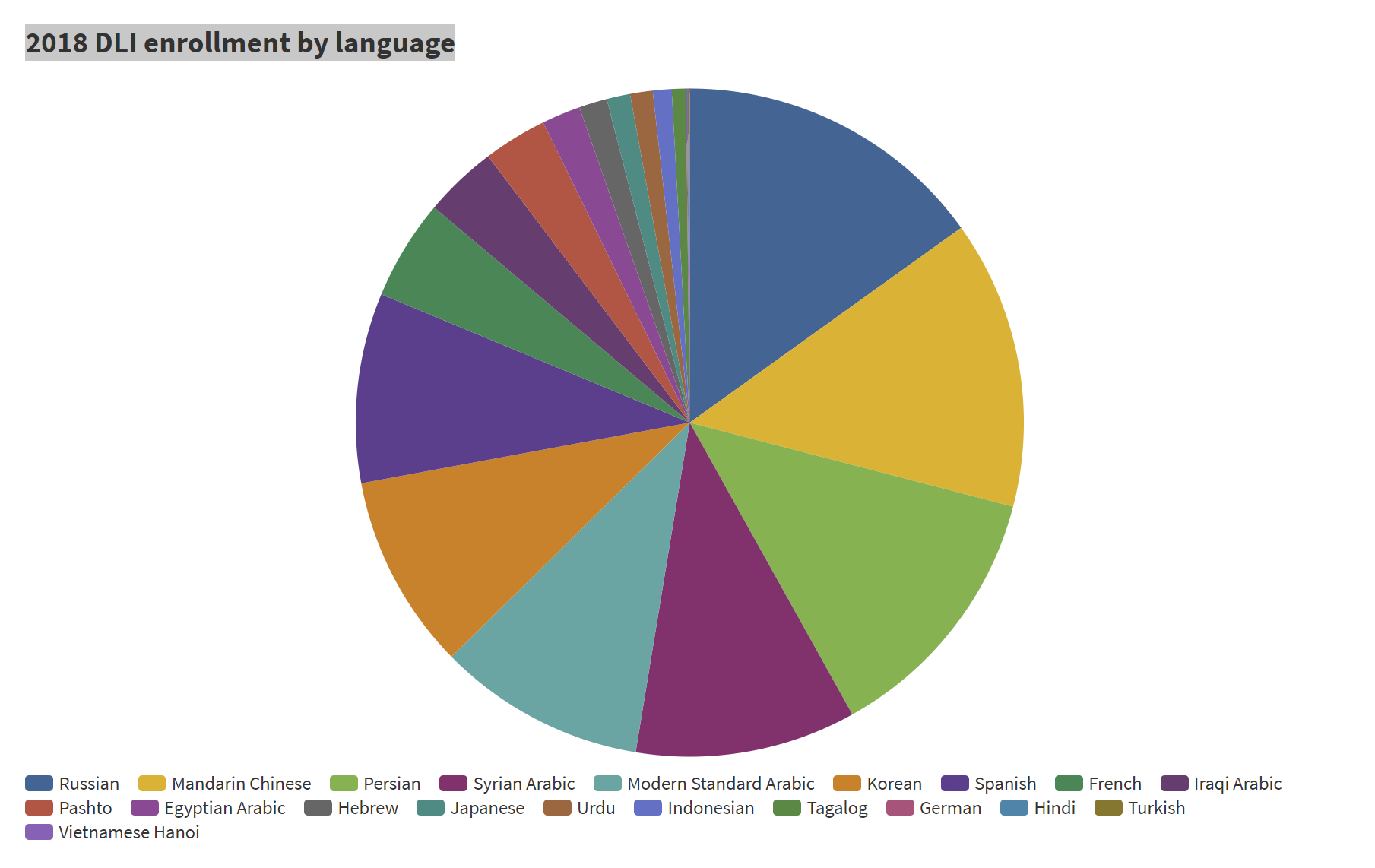

collecting enrollment figures for each language taught going back to 1963, when the school was renamed and reorganized. The data elegantly reflects the shifting trajectory of U.S. foreign policy over the years. (You can access the database yourself by clicking here.)

For example, in 2018, hundreds of DLI students took classes in languages and dialects directly relevant to the Soleimani showdown. It is more than plausible that DLI graduates took part in the operation to kill him, according to interviews with experts, including former U.S. Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta.

“I would wager that people in our intelligence teams engaged in that hard sort of work are foreign language proficient,” Panetta says. “I saw it up close when I visited our CIA stations and counterterrorism facilities.”

Iraqi Arabic is one of eight Arabic dialects taught at DLI over the last half-century. Since 2003, when the dialect was reintroduced to the curriculum after a long absence, 951 students have studied it. Soleimani was killed in Iraq but he was arguably just as active in another country of concern to the U.S.: Syria. In 2011, which is the year that the Syrian Civil War broke out, DLI began offering the Syrian-Levantine dialect of Arabic. Since then, 1,458 students have studied it. Arabic is the second-most-taught language at DLI since 1963. Soleimani’s native tongue, Persian, is in seventh place; it has been continuously taught since 1971. The data registers a sharp increase of Persian after 2003, which happens to be the year President George W. Bush named Iran, along with Iraq and North Korea, in his historic “Axis of Evil” speech.

Perhaps the clearest demonstration of how language teaching is a good proxy for foreign policy priorities is shown in the chart above (How the DLI’s focus shifts with world events). There’s a sharp drop in Eastern European languages after 1991. That’s the year the Soviet Union collapsed. Ten years later, soon after the Sept. 11 attacks, DLI ramped up the teaching of Middle Eastern languages, including Arabic, Persian, Kurdish and Pashto.

The thing about intelligence is, even when it’s there, it can be absent. Take, for example, decision-making at the White House. Panetta says the opportunity and capacity to kill Soleimani had always been there – it was a dilemma when Panetta served in the highest rungs of the national security apparatus. “We considered killing him in the past,” he says. “The reason we did not look seriously at killing him was because of the risk of war that would result. It would only serve to increase conflict in the Middle East.”

THE DLI DOESN’T ONLY TEACH THE LANGUAGES OF MIDDLE EASTERN ADVERSARIES WITH LARGE ARSENALS. It also offers, or has offered, instruction in the tongues of U.S. allies, such as Japanese, German, Dutch, Danish and Hebrew.

A little bit of history helps explain why. The Hebrew program, for example, was started up in 1986 (the data shows a handful of students in previous years). Since then, annual enrollment has averaged about 40 students, though in 2018 the figure was 30. The start year, 1986, corresponds with an event of major geopolitical significance involving Israel: Whistleblower Mordechai Vanunu exposed explosive details about Israel’s nuclear weapons program, generating interest in the U.S. defense establishment and among all world powers. But the decision to teach Hebrew would have been made much earlier, so the revelation could not have been the impetus. So what important things were happening in the Israel-U.S. relations during the early 1980s? Under President Ronald Reagan, the U.S. was in the process of ramping up military aid to Israel. The two countries signed an alliance known as the Strategic Cooperation Agreement in 1981 and began joint military exercises in 1984.

Aside from intelligence applications, foreign languages are important for communication between the commanded structure of the U.S. and its allies. “Knowing their language shows respect,” Panetta says. “We always assumed in the past that other countries would speak ‘American’ but when it goes both ways, it helps our relationships.”

Former DLI commandant Dino Pick retired from a 29-year military career in 2014, after four years at the helm of DLI, where he’d once been a student before earning accolades including a Bronze Star Medal and Combat Action Badge. (He is now the city manager of Del Rey Oaks.) He says DLI teaches more than language; the school prepares students to serve in embassies or embed with host nation militaries abroad.

“To truly understand the thinking of our allies,” Pick says, “one must speak their language, understand their culture and all of the context, including geography, economics, history. Misunderstandings can have significant national security consequences.”

THE SIXTH MOST-TAUGHT LANGUAGE IN THE HISTORY OF THE DLI IS SPANISH, a ranking that reflects the considerable involvement of the U.S. in Latin American affairs. But why invest in teaching the language millions of Americans already learn at home? It’s a question that many DLI commandants have been asked.

Sitting in his office near the top of Presidio of Monterey, the current DLI commandant, Col. Gary M. Hausman, has the most straightforward answer possible to the “why Spanish?” question: “Because that’s what the service branches are asking me to teach.” The president determines American priorities, creating the National Security Strategy. Then, the Pentagon drafts its National Defense Strategy and, eventually, the orders originating at the White House trickle down to Hausman.

The military has found it cannot meet the demand for soldiers proficient in foreign languages by tapping America’s immigrant population. It must train them.

“There’s no other way to do it,” says Pick, the former commandant. “And people try, believe me, because it’s a lot of money to train the people that we train. We have also asked, can we do it with machine translation and artificial intelligence? Can we train them in universities? Why do we need the DLI? You know, we have great universities like Stanford right up the street. Every one of those options falls flat.”

An immigrant speaking a foreign language may not know the right dialect, or might not be fluent in English, or might not make a good soldier, marine or airman, Pick says. There are always some immigrants who do serve and provide language expertise, it’s just that there’s isn’t a reliable enough stream of them to replace DLI. And saving money by outsourcing language instruction to universities might seem like a good idea, but it turns out that virtually no one can teach to the level and speed of DLI.

Hausman gives the example of an encounter he once witnessed, between someone about to graduate from West Point with a major in Arabic, and an Arabic student from DLI who was barely 18 years old and had finished high school just a few months ago. The DLI student’s Arabic, Hausman says, was at a higher level.

Kristin Sollecito

LONG BEFORE THE FOCUS ON ARABIC OR RUSSIAN, the U.S. military desperately sought expertise in a different language – Japanese. It was 1941, a few months before Pearl Harbor, and there was no DLI yet. All the military had were a newly recruited group of Japanese-Americans. They were of the Nisei generation, meaning that they were born in the United States to parents who came from Japan. The Military Intelligence Service used them as interpreters and translators throughout World War II. They served even after Pearl Harbor as the U.S. government forced many of their family members and friends out of their homes and incarcerated them in internment camps in the interior of the country.

During the war, the Army tasked Nisei translators with establishing a school for Japanese at the Presidio of San Francisco. The school was moved to Minnesota and eventually found its permanent home in Monterey in 1946. It took nearly two more decades, but eventually the Navy and Air Force discontinued their own language programs, and the Army Language School turned into the Defense Language Institute. Today, the DLI acknowledges its “intricate relationship” with Japanese Americans, as a recent brochure puts it, highlighting an evolution from “fear to solidarity.”

Three buildings on campus bear the names of nisei graduates who died in battle, and the school commemorates its Japanese-American pioneers with an exhibit titled Yankee Samurai.

c/o Department of Defense

DURING THE EARLY YEARS OF THE COLD WAR, THE MILITARY WAS SENDING MOST DLI STUDENTS TO EUROPE, which entailed transporting them to the East Coast and then across the Atlantic. There were proposals to save money on cross-country logistics by relocating the school to Fort Devens in Massachusetts or Fort Meade in Maryland. Ultimately, the Army decided against it, and a memo from 1955 describes why: “The psychological conditions… and weather at the Presidio of Monterey is more conducive for effective language training than either Fort Devens or Fort Meade.”

It’s nice to think the area is uniquely hospitable for language students, but public leaders and residents on the Monterey Peninsula often express anxiety about a possible loss of DLI to some place else. “Folks ask me about it all the time,” Hausman says. “People remember the closure of Fort Ord in the 1990s.” The military’s Base Realignment and Closure, or BRAC, process resulted in the sudden loss of that base’s population and economic contraction. Asked whether the same thing could happen again, Hausman responds: “BRAC isn’t a topic of discussion right now.”

Beyond the school’s $300 million budget, DLI brings cultural diversity to the Monterey Peninsula, thanks to its language instructors who come from 93 different countries. “There are Orthodox Christian services in Arabic,” Pick points out. “Orthodox Christian services in Syriac. There are mosques. There are temples.

“It’s a beautiful mosaic that makes Monterey unique. If you go to Santa Barbara, you wouldn’t find it. If you go up and down the coast, you wouldn’t find it.”